Do you have a dream country you want to move to? You have traveled there several times, you have figured out the paperwork, you already found a place to stay. You move there full of hopes and expectations. What can go wrong? The culture shock. It may take a few weeks or a year, it may feel like homesickness or develop into a depression. It depends on many variables but it is always there somehow. Read this guide to learn everything you need to know to prevent, recognize, and overcome the culture shock.

What is Culture Shock?

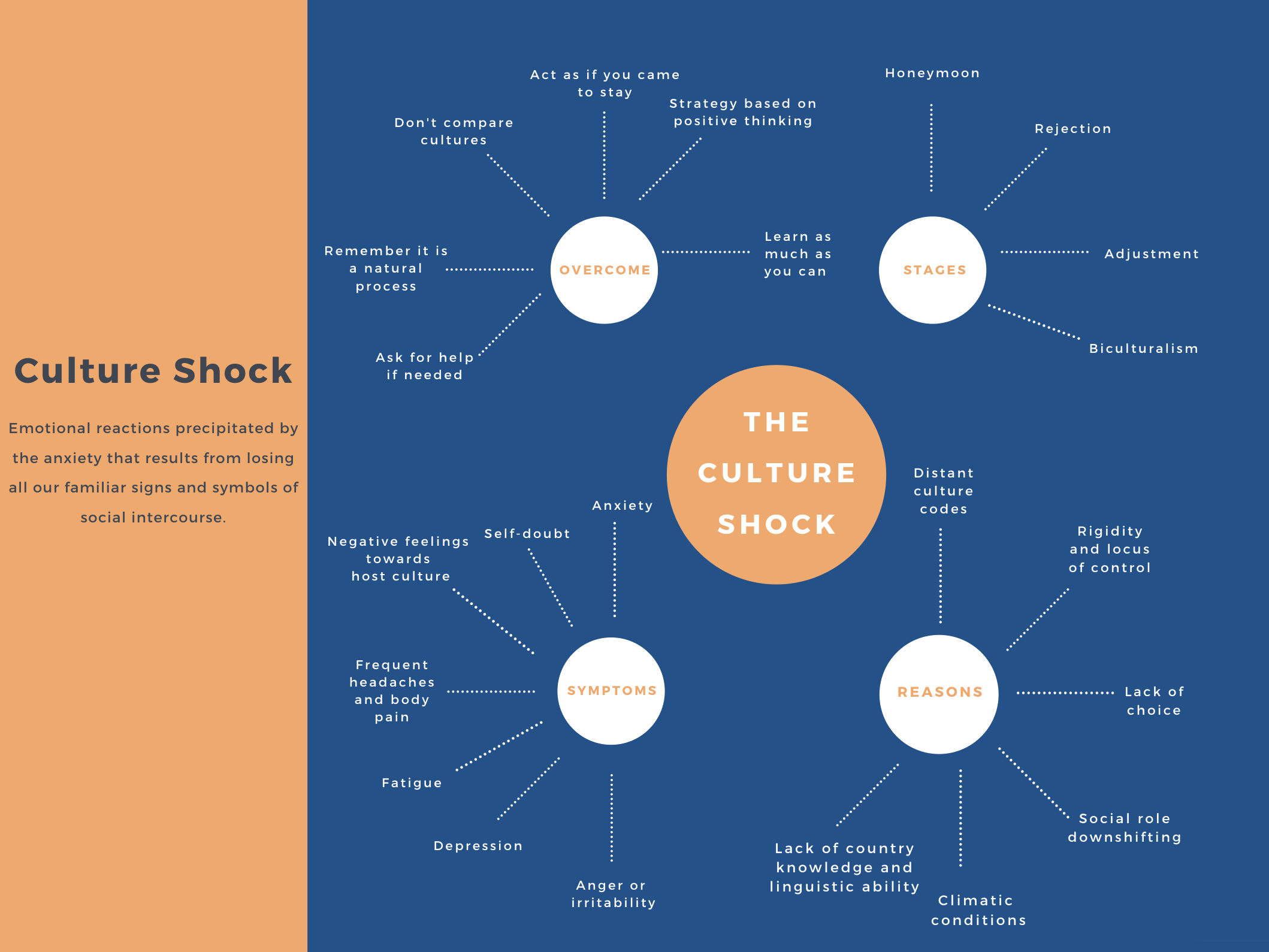

The term “culture shock” became famous thanks to a Canadian anthropologist with Finnish origins, Kalervo Oberg, in 1954. He defined culture shock as emotional reactions “precipitated by the anxiety that results from losing all our familiar signs and symbols of social intercourse”.

He pointed out how we learn to interact within the limits of our own home culture. It becomes a safe, familiar space for us. When we move to a different cultural context, these familiar cues disappear. We need to pay attention to the actions we used to perform without thinking, like greeting, smiling, social distance, the amount of eye contact. No wonders the brain can become overwhelmed.

The culture shock is not always quite a “shock” though. In the last 50 years, cross-cultural science shifted from considering it an illness to seeing it as a natural process. This is why recent studies call it “cultural adjustment” or “acculturative stress”.

Culture Shock Infographic:

Let’s learn more about cultural adjustment!

Culture Shock Stages

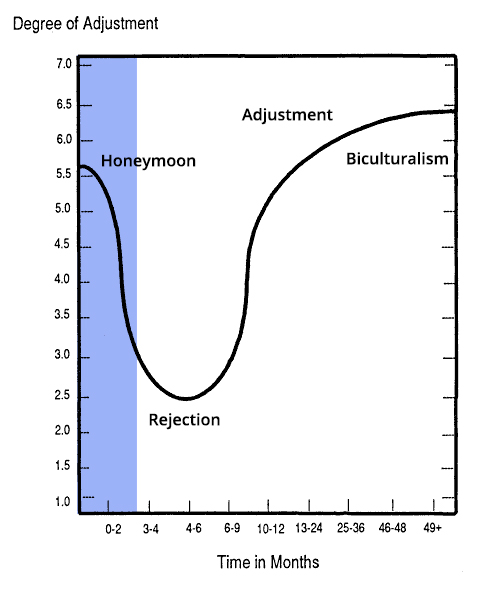

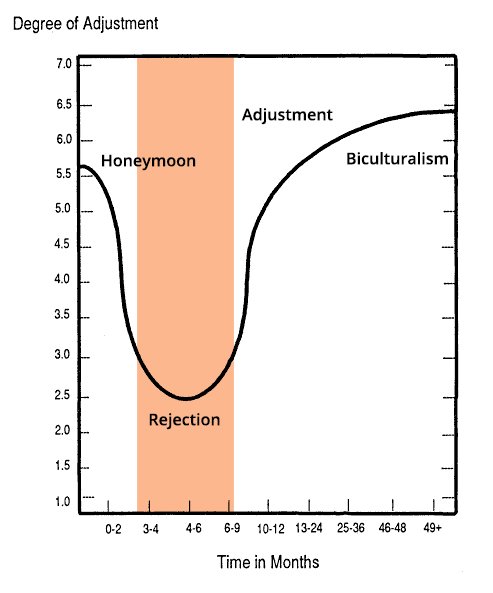

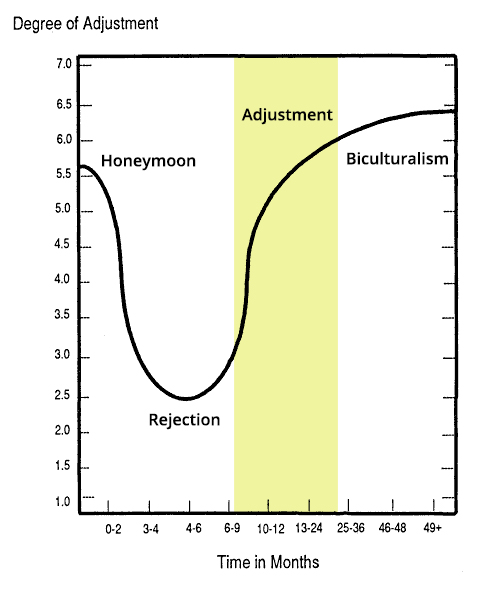

Oberg “U” Model

Oberg proposed a “U”-model of the cultural adjustment. According to this model, it gets worse before it starts to feel better. You idealize a culture, devaluate it, then end up with the cultural adaptation:

1. Honeymoon

In this stage, you experience the new culture as a tourist. You know the local culture only superficially. The differences with your home country make you curious, excited, even fascinated. You are very motivated and you want to learn as much as possible. In this phase, it doesn’t seem the cultural adjustment will ever be a problem. This part usually takes from a couple of days to six weeks.

2. Rejection or regression

In this phase, cultural fatigue starts to kick in. Now you focus on the differences between the new and the old culture. You realize that your usual cultural codes don’t work in the new environment. It makes you stressed and unhappy. You may start to feel homesick or helpless, especially if you don’t understand the language. The new culture may feel wrong, illogical, aggressive, stereotyped. At this stage, you get frustrated even for small issues. Prejudices of your home culture about your target culture surface. Expats who generalize criticizing locals are usually at this stage. The refusal to learn the local language may arise as a defensive mechanism: “If I don’t understand you, you can’t hurt me”.

In this phase, cultural fatigue starts to kick in. Now you focus on the differences between the new and the old culture. You realize that your usual cultural codes don’t work in the new environment. It makes you stressed and unhappy. You may start to feel homesick or helpless, especially if you don’t understand the language. The new culture may feel wrong, illogical, aggressive, stereotyped. At this stage, you get frustrated even for small issues. Prejudices of your home culture about your target culture surface. Expats who generalize criticizing locals are usually at this stage. The refusal to learn the local language may arise as a defensive mechanism: “If I don’t understand you, you can’t hurt me”.

People from the new country seem cold, unhelpful, you don’t trust them. In fact, locals might respond to your interiorized hostility betrayed by your body language or other small signs you are unaware of. Many expats look for compatriots or someone who speaks their language(s) and hang out with them more.

Other people emphasize only the positive sides and deny even to themselves that they experience some difficulties.

3. Adjustment or negotiation

After a while, you learn the core values of the new country, the rules of social interaction, the cultural cues. You know the local language a bit better and you have some good memories of your new city. Your social circle expands and you don’t feel lonely as much as you used to. You feel more comfortable and start to see the positives again.

After a while, you learn the core values of the new country, the rules of social interaction, the cultural cues. You know the local language a bit better and you have some good memories of your new city. Your social circle expands and you don’t feel lonely as much as you used to. You feel more comfortable and start to see the positives again.

It feels like you can laugh at problems that seemed insurmountable months ago. You begin to be aware of your home country values you used to take for granted. You may even start to question some of them.

4. Adaptation and biculturalism

In this phase, the new culture feels like another home to you. You can live, work and be happy in your new reality. In the XXth century, assimilation was an expat’s best option. Scientists thought that to be happy in a country, you must embrace all its values and beliefs. Now, this is no longer the case.

The latest studies show that the adaptation process makes people happy but their home culture matters too, it doesn’t have to disappear. On the contrary, it is an important part of identity and it has to be kept. The best way to adapt is to balance between the cultures.

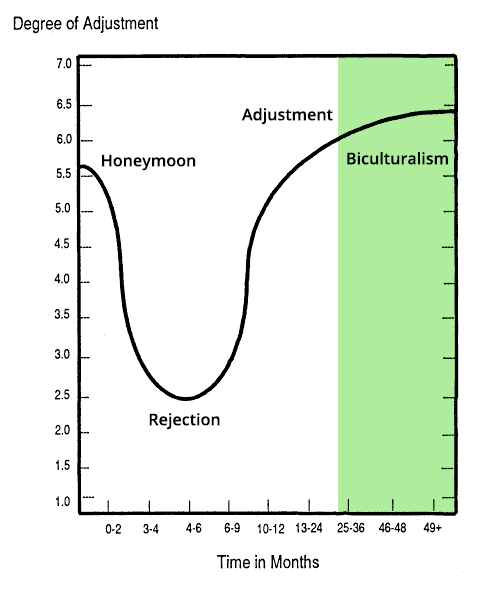

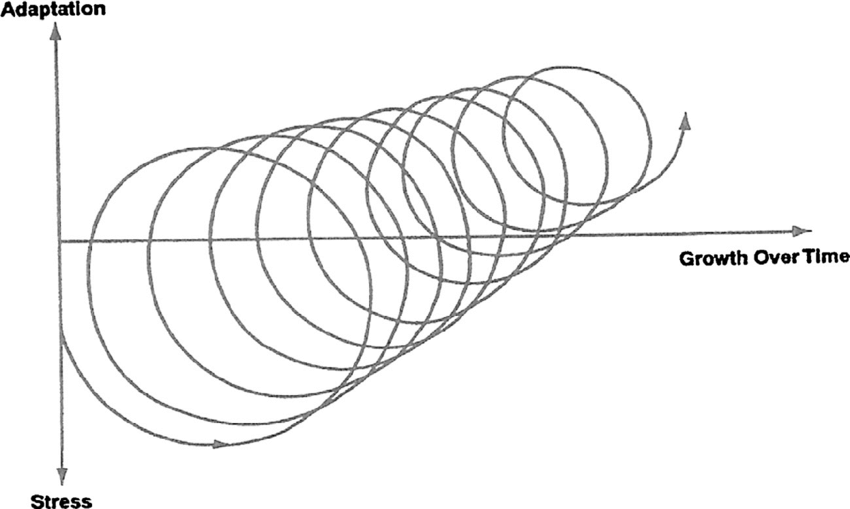

Young Yun Kim “stress-adaptation-growth” model

In an alternative to the U-model, the Korean-American professor Young Yun Kim proposed a “stress-adaptation-growth” visual model in 2002. According to her theory, we never actually fully adapt. We make one step forward and two back and it is fine to feel distressed, sad, or homesick from time to time, but each time it will be more manageable and less intense.

This theory applies the most to what’s going on with a long-term established in another country person.

What are your chances to experience culture shock?

-

Objective conditions. Was the relocation your choice? Do you like the new country? How will your life change? A teenager who didn’t want to move far away from their friends, a refugee or an economic migrant will be more affected by the acculturative stress than a professional who relocates to Rome willingly to work for FAO. The “country of your dreams” aspect can affect you too though: if you idealize the country too much, you might not expect its downsides.

-

Relocation period and social role. If you move for a language course or a Ph.D., you know you are only there for a couple of years. Same for embassy employees or temporary English teachers. You don’t feel much pressure because you will have around people who speak your language, and you already have an occupation that defines you. Also, if you don’t like the new culture, you can choose to stay in your bubble. If you move for a lifetime, following a partner or your parents, there is usually much more pressure. It is even bigger for economic migrants or refugees. Not only have they to figure out how a new culture functions, but they must also do it quickly, to find ways to provide for themselves and their families.

-

Climatic conditions. You may want to escape your cold city telling yourself that you love the sun, only to discover later that 40°C/104°F feels like too much. Especially if you moved to your sunny destination in winter and didn’t consider renting a place with air-conditioning. Same if you are not used to several months of rain and cold. You may unconsciously project your physical discomfort in the target culture and even into local people.

-

Intercultural experience. If you grew up in a cross-cultural context, moved a lot, had relationships with people from other cultures, you already know what to expect. If you come from a very ethnocentric culture with little diversity, the cultural adjustment will take more time.

-

Previous knowledge about the target culture and your linguistic ability. The more you learn about the differences between the cultures and master the local language(s), the better you will decode the behaviors and minimize misunderstandings.

Previous knowledge about the target culture and your linguistic ability. The more you learn about the differences between the cultures and master the local language(s), the better you will decode the behaviors and minimize misunderstandings.

-

Relationships with locals. If you move to a new country by yourself, it will take some time before you make new meaningful connections. If you follow a local partner who can introduce you to their established social circle, it might be easier to adapt.

-

Tolerance of ambiguity. Chances are at the beginning of your journey, you will feel a lack of control many more times than you hoped to. If you perceive ambiguous situations as desirable, you will focus on learning instead of resisting them. It will make your integration process much easier.

-

Locus of control. People with an external locus of control attribute their successes to luck or fate, while those with an internal locus of control believe they control their lives. Some studies link the external locus of control to more cross-cultural difficulties. If you blame your fate or the locals instead of focusing on the integration process, it doesn’t do you good.

-

Rigidity or tolerance. Open-minded people, who embrace diversity and are ready to change, face new experiences with enthusiasm. Rigid people who change at a slower pace usually resist the new culture longer.

-

Similarities between the culture of origin and the new one. For a Spaniard or a Latin American moving to Italy won’t be a huge cultural shift. For a Japanese or a Russian, Italy feels more challenging because of the distant culture codes. The more exotic it seems to you at the beginning, the bigger your chance to feel culturally fatigued. A Finnish study showed that people who came from countries with a similar background, usually adapted after a couple of months, while those who came from a different cultural background integrated after 1,5-2 years.

-

How do locals perceive your home culture/country? Not everything in your adaptation process depends on you. If locals perceive your country of origin in a certain way, it will be more difficult for them to learn to see the individual, not the stereotype in their heads. If you are a Russian who moved to Italy, you will have to explain why you feel cold in the winter all the time. Moving to a country with a visibly different phenotype adds another dimension to your cultural adjustment. Even if locals are friendly and genuinely curious about your home culture, being labeled as a foreigner most of the time may cause distress and identity issues. They are even more accentuated in second-generation children and teenagers. They grew up in a country and identify with its values but are continuously reminded of their phenotypical difference.

-

The willingness of the new country to ease adaptation. If the new country has cross-cultural programs to help expats or refugees, the adaptation process will be smoother.

What are the culture shock symptoms

- Fatigue. This is one of the most common symptoms. Your brain has to work on the smallest things that used to feel safe, that’s why you feel this way. You may need more sleep, feel numb, and overwhelmed with the smallest issues.

- Anger or irritability. When you blame the members of the other culture for your negative feelings or expect the worst from your social interactions, try to remember why you came to this country in the first place. Don’t blame yourself too much for feeling this way though, it is part of the process.

- Depression. If you frequently feel extremely vulnerable, sad, lonely, lost, and helpless, you should ask for help.

- Anxiety. You might fear for your health, of being cheated or robbed. Some obsessive-compulsive behaviors may arise to get some control back. Try mindfulness or counseling to reduce anxiety.

- Frequent headaches and body pain. You can experience sleep disturbance. Chronic illnesses may reemerge, especially skin-related issues. Anyways, it is good for you to learn right away how the medical system works in the new country. Make a path to follow in case of emergency, with useful numbers to call and doctors or cross-cultural specialists who speak your language.

- Negative feelings towards your host culture. If you criticize locals, feel above them, stereotype them and their culture and hang out only from people from your country or with fellow expats, it will slow down your integration process. On bad days you need your familiar interactions to rely on, but getting to know the new culture is key for integration.

- Self-doubt. If you feel shy or insecure, or if you question your decision to move to this country and blame yourself for not reaching your goals as fast as you planned, take a break. It is normal to question your usual beliefs when you learn something new but don’t question yourself. You are doing the best you can. And it will get easier, promise, I’ve been there too.

How to Minimize and Overcome Culture Shock

- Remind yourself that this is a natural process. If you feel some of these symptoms, you are human. Most people experience at least some of them when they have to deal with a new culture on a daily basis. If you don’t feel any of these, you might be between those few lucky people who experience culture adjustment as a positive process only.

- Bring with you something that might help you cope for the first months. It may be your favorite food from your home country, your toy from when you were a child, or some family photos.

- Learn as much as you can about the local language(s) and culture(s). Studies show that people who study the language and the traditions of their new culture beforehand are happier than those who don’t. Watch their movies, read their magazines, try to understand their humor. You will need all of that in your conversations.

- Be open-minded. As said below, rigid people have harder times abroad. Curiosity and acceptance will help you make friends and feel like home.

- Act as if you came here to stay. When we face culture shock we may spend a lot of time ruminating about the future. Will we stay here, move somewhere else, or return home? It is better for your mind if you convince yourself that you came here to stay. This little trick gives your mind the necessary motivation and helps you integrate faster.

- Try to not compare culture. “The food in my home country was so much better, how can they eat this?” See? This is you judging and thinking. The less you compare cultures, the better. They are different and they are both ok.

- Try to figure out the core values of the new culture. Do you know this image of Italians as always having a dolce vita lifestyle all the time? Well, that’s what people see on the surface, but this is not true. They do enjoy their work-life balance, but they can also quite competitive in the workplace. You just need to be an insider to observe that. And lots of other things.

- Bond with locals. There are some people in this country who are in love with your home culture or language, locals who are into your hobby too. Try Facebook groups, gym, courses, or dating. You will eventually find your people.

- Focus on the similarities. Besides the cultural differences, all humans experience the same basic emotions. You can bond on this. They may express their feelings differently and you will learn that in time but I assure you, they feel the same way you do. They want to be loved and appreciated, they enjoy genuine interest and complements, they are afraid to embarrass themselves and they want to make a good impression. Just like you, right?

- Be aware of your prejudices and stereotypes. If you think about people in a certain way, you are likely to behave as if they were like that and this is not always the case. Not all Germans are punctual and not all Italians gesticulate a lot. Learn more about the individuals you interact with.

- Remember that there is more than one concept of what is normal and right. If people in the new country do something in a different way it doesn’t mean it is wrong. They do sort things out, don’t they?

- Get a conscious adaptation strategy based on positive thinking. Make a realistic plan and stick to it. Remember you can do this.

- Ask for help if you feel that you can’t cope. It is better to find a psychologist who can speak your language online than spiral into depression. The sooner, the better.

- The negative part of it will decrease in intensity and eventually end. Studies show that it takes people from a few months to a maximum of 4-5 years in some rare cases, to overcome the culture shock.

- Find a cross-cultural training to learn more about the new culture. One training can save you hours of research and give you so many useful insights.

- It might be hard now, but you will eventually become a more complex and integrated person. Being multicultural will boost your confidence, help you in conflict situations, and will improve your life in so many ways!

- Know when to stop. If you tried everything and this country just doesn’t seem the right place for you, maybe it isn’t. Study your options and do what it takes to be happy! Take my Culture Test to discover the right country for you.

Cultural adjustment test

Answer these 5 questions honestly to discover where you are in the integration process:

- Are you fluent in the language of the country you moved to?

- Do you have a job with locals or another job in the new country?

- Do you know how to interact with social institutions – shops, hospitals, gyms, concerts, etc.?

- Is your attitude towards locals positive or neutral? Do you have friends among them?

- Did you maintain some traditions and manners from your home culture?

If you answered yes to all the questions, you are on the right path of integration. This is the most successful strategy to be at ease in the new country with respect to your home culture – when you care about your past and are ready for your future.

Did you experience culture shock? How did you overcome it? Comment below!

If you like this project, subscribe to the Multicultural You newsletter. I hate spam and will send you only one mail per month full of useful intercultural information!